[Update: Fixed header tags, added revenue graph and concluding paragraph]

The fever-pitch intensity of an election year has given way to Hurricane Sandy relief efforts, followed by the Newtown shootings and a smorgasbord of exciting new strains of flu virus and other such transmittable delicacies.

Now that the dust is settling from the fiscal cliff negotiations, it might be useful to take a moment to consider where we are politically and economically, and what that may mean in terms of our next steps. I will focus first on the recently completed “fiscal cliff” deal–what’s in it and who’s affected by it.

The “Fiscal Cliff” Deal

The “fiscal cliff” standoff resulted in a deal including the following:

- Bush tax cuts made permanent for individuals earning less than $400,000 per year/households earning less than $450,000 per year;

- Capital gains: increased from 15% to 20% for individuals earning over $400,000, households earning over $450,000;

- AMT patch is extended for 10 years;

- Estate tax rate increases from 35% to 40%;

- Sequester delayed by 2 months;

- Doc fix enacted for one year;

- Unemployment insurance extended for one year;

- Farm bill extended temporarily;

- Spending and revenue offsets: about $50 billion enacted to pay for delay in sequester and doc fix;

- Expiration of the payroll tax holiday

Source: The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB)

Who is Affected by the Deal and How?

Despite the increase in top marginal tax rates, the wealthy will continue to do quite well. While individuals earning over $400,000 per year and households earning over $450,000 per year will see a rise in their marginal tax rates, they will enjoy a cut in taxes below the marginal rate, just like everyone else. Thus an individual earning over $400,000 per year will pay a 39.6% tax on the amount over $400,000, but a 25% tax on the amount between $35,350 and $85,650, and so on. In addition, as Matthew O’Brien notes, raising the estate tax is a matter both of tax fairness and revenue. Simply allowing the estate tax to revert to Clinton era levels would have yielded $375 billion more in tax receipts than will come from the fiscal cliff deal of a $5 million exemption and an estate tax rate of 40%, which is a huge giveaway to the wealthy.

The extention of the doc fix will benefit doctors receiving Medicare payments.

The elderly have been spared, at least temporarily, from the draconian cuts to Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security championed by the GOP.

Another extension of unemployment insurance will benefit the unemployed. On the other hand, expiration of the payroll tax moratorium means those taxes will go up for working people–a large segment of the population.

What are the Budget Implications of These Changes?

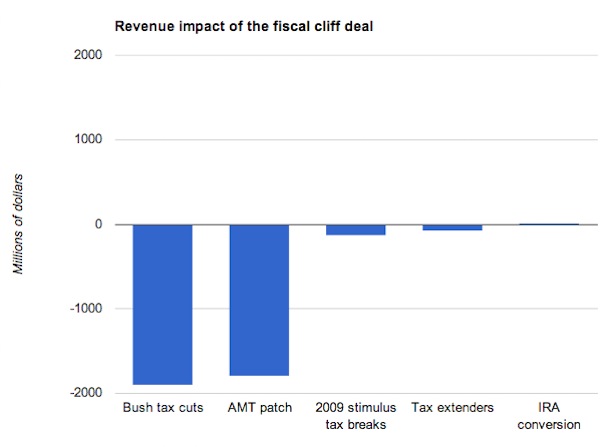

The Tax Cuts

As Joe Weisenthal notes, “The difference between the Obama Tax Cuts and the Bush Tax Cuts? Obama’s are permanent.” And Brad DeLong observes that “[u]nfunded tax cuts are, in the long run, bad juju. We cannot make policy on the expectation that the U.S. will always be able to borrow at negative real interest rates. And we should make policy aiming for a low debt-to-GDP ratio, because emergencies will arise in which we will want to boost federal spending quickly and substantially to attain important national purposes.” Yet he sees no obvious policies that will fund those tax cuts.

Think about what it took just to end the Bush tax cuts for the wealthiest 2% of the population. Consider that and DeLong’s statement about the need for a low debt-to-GDP ratio, and bear in mind that the US had, before the fiscal cliff deal, the lowest personal income tax rates of any industrialized nation (and some of the lowest social spending as a percentage of GDP, not coincidentally). What do you think it will take to raise taxes in the future, after the economy returns to full strength, as we try to pay down the deficit and debt? And if we cannot increase revenues via taxation, what choice will we have but to slash federal spending? That is the logic behind the GOP’s starve-the-beast approach to tax policy–an approach that has just gained additional power.

Deficit and Debt Reduction

The CRFB, a center-right organization focused, a la Pete Peterson, on reducing the deficit and national debt, sees positive results in (a) the postponement of drastic sequestration cuts; (b) the increase of $620 billion in federal revenues resulting from tax increases; (c) establishment of the “precedent that extending the sequester has to be paid for and strengthen[ing] the precedent that the doc fix should be waived only along with offsetting health provisions;” and (d) the possibility that lawmakers can find alternatives to the upcoming sequester.

They oppose the absence of (e) debt stabilization measures; (f) “serious entitlement reforms;” (g) “a process to enact pro-growth and revenue generating tax reforms;” or (h) offsets to the costs of tax extenders and unemployment insurance benefits. In addition, they deplore (i) the $4 trillion cost of making the Bush tax cuts permanent and extending the AMT patch; (j) use of a gimmick to pay for the sequester; and (k) what they term the missed opportunity to provide a comprehensive debt reduction package.

Underlying their dedication to budget cutting are fears of inflation and that high deficits will soon result in the government “crowding out” private investors as it borrows increasing amounts of money from the federal reserve to pay the interest on the national debt.

Unlike the CRFB, Pete Peterson and other so-called deficit scolds, economists adhering to the Keynesian approach to recessions such as Paul Krugman, Brad DeLong, Robert Reich, and Mark Thoma, argue that cutting government spending at this point is exactly the opposite of what should be done during a slowdown. They argue instead that renewed federal stimulus spending at a time of historically low interest rates and inflation would boost the economy, resulting in increased tax receipts that would go toward paying down the deficits and, eventually, the debt. They also note that there are no signs of inflation and that interest rates are at historically low levels. Accordingly, they disagree with the CRFB on point (f) above in particular, and are highly suspicious of the grand bargain touted by the deficit scolds. In general, this latter group of critics is highly critical of the fiscal cliff deal’s extension of tax cuts to the $400,000/$450,000 limit.

Economic Implications

The deal offers little in the way of economic stimulus to the economy. In fact, economist Brad DeLong estimates that the deal will reduce GDP this year by about 2%. While unemployment insurance has been given another one-year extension, the payroll tax cut has ended. Meanwhile, unemployment is about 7.4% and GDP growth remains much lower than the level needed to create enough jobs to bring the millions of people unemployed by the Great Recession back into the workforce.

Meanwhile, Robert Greenstein notes that the deal represents a modest slowdown in the rate of increase in income inequality.

Conclusion

The bottom line, in budgetary and economic terms, is that the deal largely preserves the status quo. While deeply disappointing to budget hawks and others seeking to use high deficits and debt (which the GOP racked up intentionally as part of their starve-the-beast strategy), the fiscal cliff deal has preserved unemployment insurance for another year, spared the elderly and the poor from draconian cuts to programs they need, and avoided, at least temporarily, the most recessionary effects of austerity budgeting.

Glossary

AMT (Alternative Minimum Tax): This was established to prevent the wealthy from paying taxes. However, it was never indexed for inflation, the result being that the AMT now applies to many middle class families. If the AMT were allowed to expire, many middle class families would end up paying significantly higher taxes.

Austerity budgeting: The idea that imposing sharp spending cuts during an economic downturn will lead to the elimination of deficits, paydown of debt, and a dramatic increase in economic growth.

Debt: The sum of accumulated deficits.

Deficit: The gap between federal income & federal spending in a given fiscal year.

Doc fix: An annual measure to prevent a reduction in Medicare payments to doctors.Fiscal cliff: The combination of expiration of the Bush tax cuts & imposition of sharp federal spending cuts imposed as a way around the 2011 debt ceiling standoff facing the US at the end of 2012.

Marginal tax rates: The tax rate paid on income within a specific income bracket.

Sequestration: The package of sharp cuts in federal spending imposed as a way around the 2011 debt ceiling standoff.